Although our decision to add a fourth year of breeding surveys to the atlas project was mostly based on the developing pandemic, another key variable we considered was how close we are to having enough data for the project to be a success. Of course, “enough” is a relative term, so we had to choose criteria to determine when a block should be considered complete. At the start of the study our goal was to have at least 20 hours of breeding season surveys in each block, with at least a couple of those at night listening for nocturnal birds. This approach is typical of many atlas projects. If someone spent all 20 hours at the same site in May, however, their data would not give us all that we hope to get from the project. Consequently, we have added two additional criteria – a measure of the number of species found and a measure of the number of species confirmed – to give us a more rounded assessment of block completion.

Because we expect variation among locations in the number of species, we based our target measure for a given block on the number that was detected there during the first atlas – with a goal of finding at least 80% of that target. And, because we know it is much harder to confirm species than to simply find them in suitable breeding habitat, we set the completion goal as just half of the species found. Clearly, all three benchmarks are somewhat arbitrary, but collectively we believe they will provide a good indication that a block has had sufficient field work, appropriately spread out across time and space, to ensure representative information about the birds that are found there.

To calculate block completion we simply estimate how close we are to meeting each criterion – 20 hours of survey effort, 80% of the species found during the 1980s atlas, and at least 50% of detected species confirmed – and determine the average. There is nothing to stop someone from continuing to collect data once these targets have been met, but in general we believe that time is better spent working in less well surveyed blocks once that average reaches 100% (more on that in the next post).

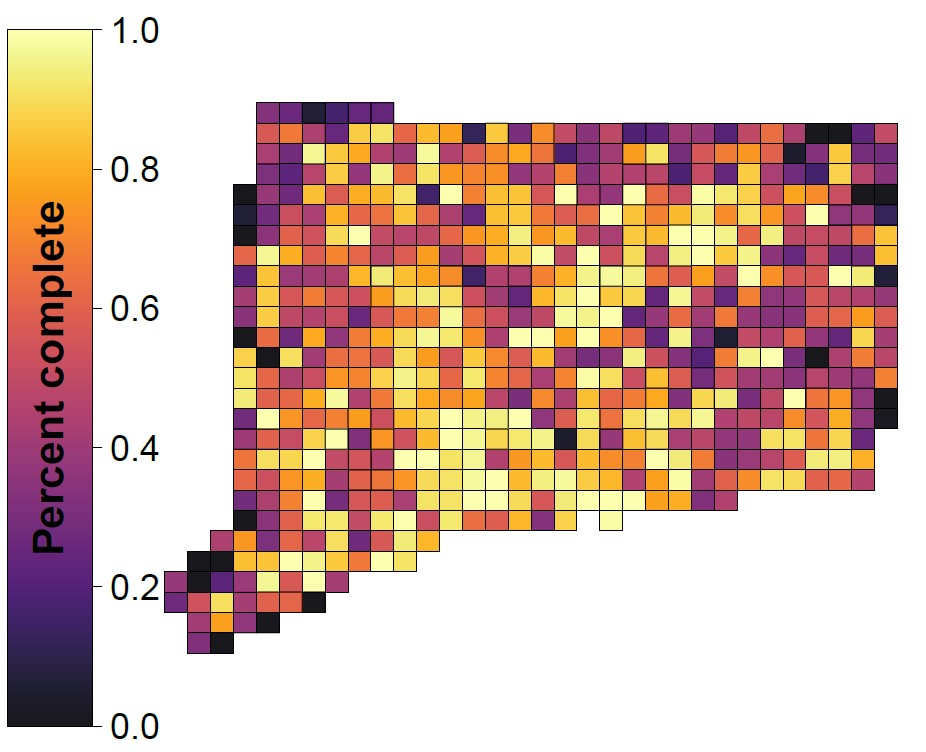

The resulting block completion map is both very encouraging and highlights a lot of work still to do.

Block completion at the end of the 2019 breeding season. Pale yellow blocks indicate 100% completion, while black blocks are those that have received little or no survey effort.

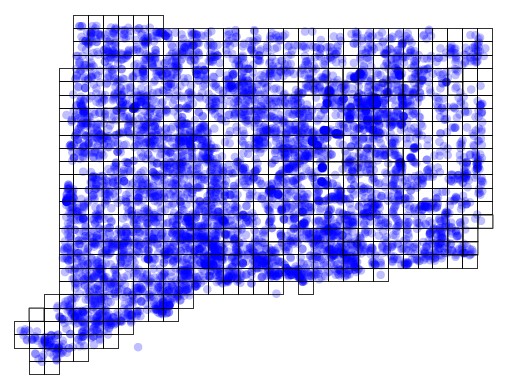

Not surprisingly, blocks in heavily-birded, and heavily-populated areas are either complete, or close to it. Blocks farther east, farther north, or at the periphery of the state, are most likely to need substantial work. None of this will be a surprise to anyone who has been tracking our updates of where atlas data are being submitted from, the latest version of which is shown here:

Updated distribution of breeding season checklists shared with the Connecticut Bird Atlas between the start of the 2018 breeding survey and March 2020. Each blue dot represents a location where at least one checklist has been submitted.