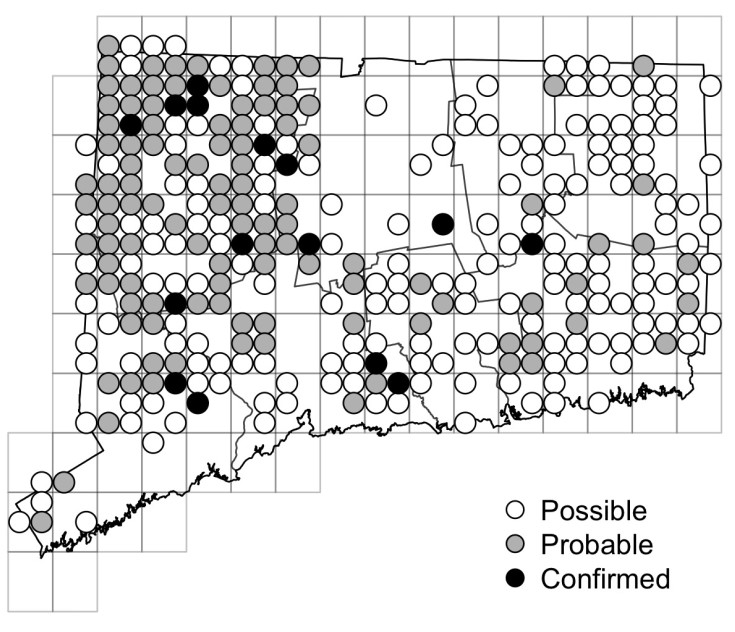

One of the goals of the Connecticut Bird Atlas is to document changes in distributions since the first atlas was done in the 1980s. At that time, turkey vultures were widespread, but breeding was concentrated in the western half of the state, away from the coast, and winter concentrations were still noteworthy. Black vultures were considered very rare, with no evidence of breeding recorded during the atlas, although they were starting to be seen more frequently. Both species have increased. Just how much, is something we hope the new atlas will tell us.

Distribution map showing breeding records for turkey vulture during the 1980s Connecticut atlas.

Documenting nesting in vultures, however, can be a challenge. During the five years of the recent Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas, turkey vulture was confirmed in only 19 of 1056 blocks (less than 2%) and black vulture was not confirmed at all. With that in mind, it is worth everyone knowing the tell-tale signs that a vulture might be nesting nearby.

Both species nest in a variety of cave-like settings. Often these are real caves or crevices among rock outcrops, but birds will also use hollow trees, mammal burrows, dense thickets, and abandoned buildings. To see the diversity of sites, follow links to these YouTube videos (nest 1, nest 2, nest 3, nest 4). The eggs are laid directly on the floor, and sites are often used year-after-year. Most birds also stay with the same mate until one dies – perhaps ten years or more. The parents share incubation duties, switching off once a day, usually in the morning between 8 and 10.

Although, it is early days for the Connecticut project, we have already learned of two black vulture nests, both in rocky outcrops in forested areas, and both found when someone walking past happened to see a bird hop out of a crevice and stand on the rocks nearby. In one case, the bird disappeared again, only to remerge as the observers got closer, then fly quietly up into a nearby tree to watch. In the other, the bird hissed and made clear its displeasure at the intrusion. Similar behavior has also been observed by a turkey vulture in a similar setting, close to one of the black vulture nests.

Black vulture just after emerging from the rock crevice in which it is nesting.

So, if you come across a vulture acting furtive or hissing aggressively, while you are hiking through the woods, there’s a good chance that there’s a nest nearby. If a nest can’t easily be seen – which is likely if it is deep in a rock crevice, high in a tree, or somewhere in the depths of a falling-down barn – it is worth returning at 8 am, or earlier, and patiently watching from a distance for a couple of hours, to see if you can observe the adults exchanging parental duties. A visit a few weeks from now might even be rewarded with young birds exploring the area around the nest.

In another setting, turkey vultures that are apparently nesting in an abandoned barn are routinely seen flying low over the building and nearby trees, which is perhaps another tell-tale sign that could be used to identify potential nest sites.

One of the Connecticut nests already has chicks, but vultures develop slowly, and the young may not emerge from the nest until they are almost two months old. They may not make their first serious flights for a couple of weeks beyond that. So, there remains lots of time to confirm breeding in these species and help us better understand just how much their breeding distribution in the state has changed.

Black vulture eggs in a rock crevice.

Black vulture chick; photo taken with red light to reduce disturbance.

Thanks to the finders and photographers on these birds for passing on their careful observations and sharing their photographs.

To learn more about the historical occurrence of vultures in Connecticut, check out Connecticut Birds by Joseph Zeranski and Tom Baptist and the first Connecticut atlas by Louis Bevier. For more on the breeding biology of the two species read the Birds of North America accounts by Neil Buckley (black vulture) and David Kirk and Michael Mossman (turkey vulture).