When we started the atlas, we told everyone that our goal was to have 20 hours of breeding season survey effort in each block. That time could all be spent by one person who “adopts” the block, or it could be from a mix of people. And, we asked that the time be spread evenly across the breeding season, including visits to all habitats, and with at least a little time listening for nocturnal species. Although we don’t have detailed information about how much time was spent in each block during the 1980s’ atlas, 20 hours is a typical recommendation for atlas projects, and so we thought that that was a good goal.

When we sat down this winter to see what our project stats looked like, we realized that – although we were well on track in many respects, the average number of confirmed species was lower than we’d expected. During the first atlas, ~50% of species were confirmed in a typical block, so that was what we’ve been viewing as a good target (hence our use of that value in our “completion statistics“). Our expectation was that we would get that with the 20 hour commitment, and in many cases we have, but our initial results suggest that things are more complicated than we’d assumed. Now that we’ve dug a little deeper into the data, we think we understand why we have fewer confirmations than expected.

Observing young birds, recently out of the nest – like this young American robin – is one of the easiest ways to confirm breeding.

Confirming species is always much harder than simply finding them. Nests are, purposefully, hard to find. To make matters worse, searching for them can run the risk of disturbance, which none of us want. By far the easiest way to confirm breeding in most species, is by seeing adults collect big beakfuls of food, and then carrying them repeated to the same spot (code CF) – where the nest is somewhere hidden. Or, by seeing (or hearing) newly fledged young either on their own (FL) or being fed by a parent (FY).

Unlike most birds, this chickadee is obligingly standing on its nest, which is out in the open and right next to my backdoor. Even if it were not, though, I could confirm breeding because I see it flying across the patio with food every few minutes.

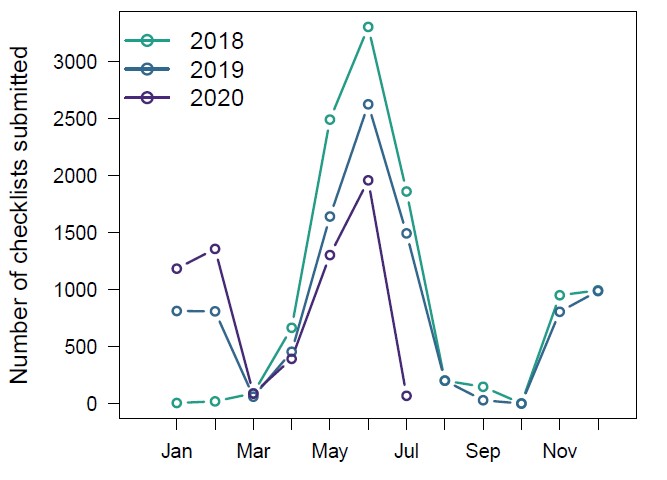

For most species, the best time to observe these behaviours is from late June into early August. In other words, the next 4-5 weeks are critical for confirming a majority of species. But, when we look at the data, we see this:

The graph shows the number of checklists submitted each month, in each year of the project. The line for 2020 is lower than those for the first two years – partly because we’ve not yet entered data submitted via methods other than eBird, and partly (we suspect) because people have been suitably circumspect about birding too much given the ongoing pandemic.

The most important part of this graph, though, is that it shows that during the past two years, the number of surveys has dropped considerably in July. Given that this is the best time to see adults carrying food or to find fledged young, we suspect that this explains why confirmation rates are not higher.

So, the message is not so much that we should be spending more time atlasing, but that we should be spending more of our atlasing time going out in July. Clearly, that is easier for some people than others – and we are not suggesting that anyone put in time that they can’t afford (atlasing should always be fun, not a chore!). But, for those who have time to go birding over the next few weeks, know that this is the month when you can get the biggest bang for the buck in terms of high value data collection.