Yesterday, I wrote about a way that birders can help with a student-led project designed to study the effects of forest fragmentation on woodpeckers and other bark feeding birds. Today, I thought I’d give an update on what the atlas data show us, so far, about the distributions of woodpecker species in the state. As usual, all results are preliminary and incomplete, both because data are still flowing in and because they have not been fully checked. Nonetheless, we’re starting to get a picture of what the atlas will tell us.

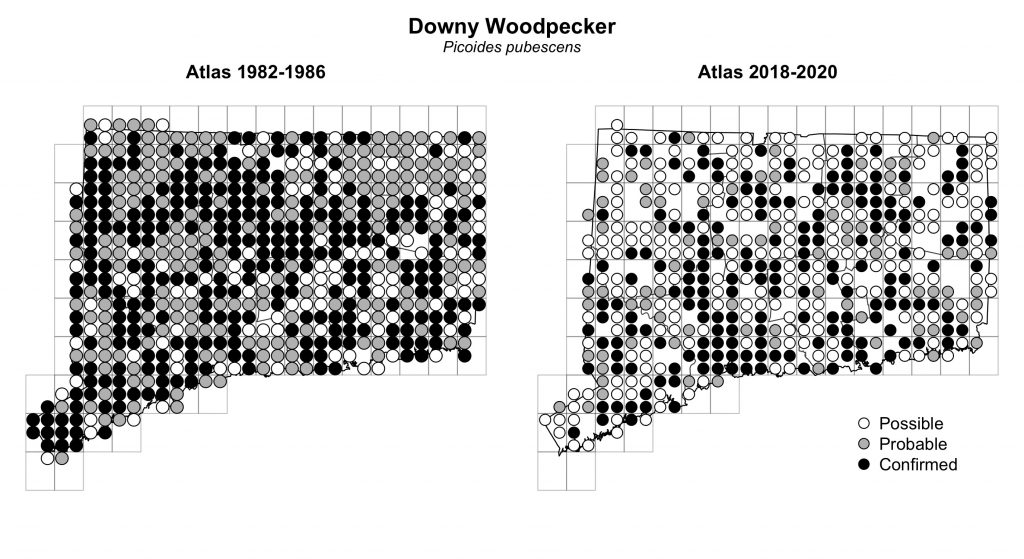

Downy woodpeckers appear to show similar patterns to the 1980s, albeit with fewer confirmations and more gaps – both of which may simply be due to less birding effort as we are still only part way through the study:

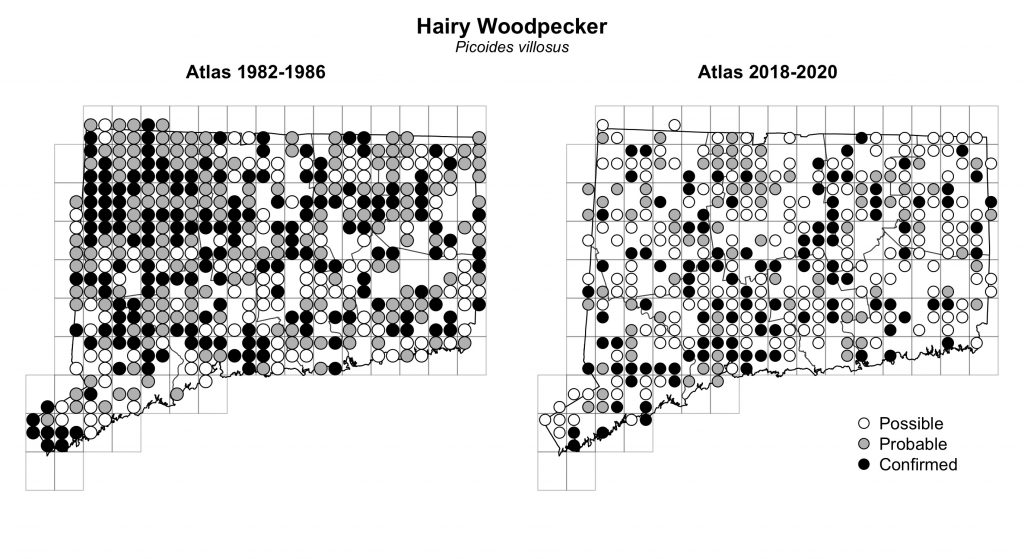

Hairy woodpeckers show a similar story, although the lack of records in the NW corner of the state potentially indicates a real decline:

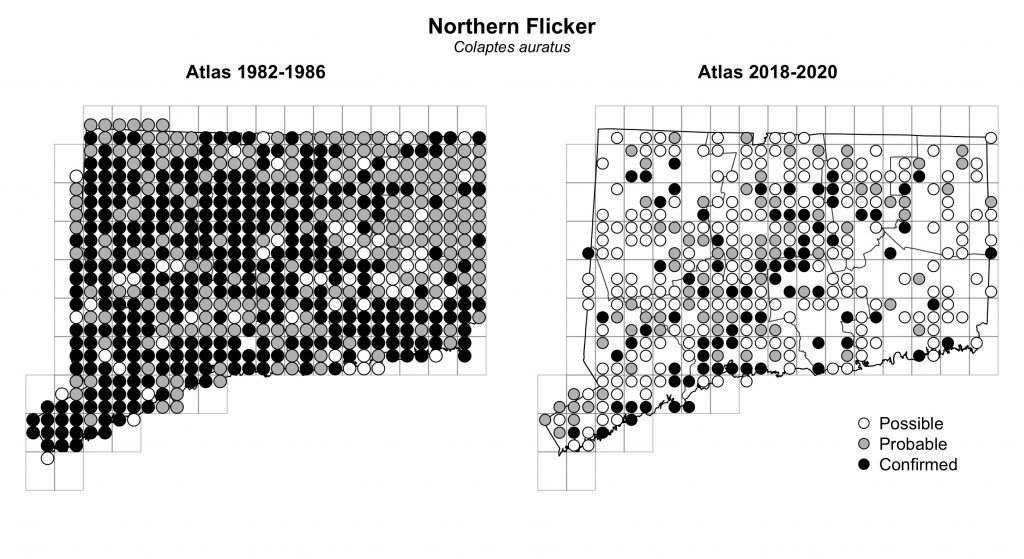

For northern flickers, the evidence for a decline is much stronger. It’s too soon to be sure – and a more detailed analysis will be conducted when we’ve finished data collection – but this clearly looks like a species we should be concerned about (as also indicated by USGS Breeding Bird Survey data from Connecticut and from eastern North America in general):

For northern flickers, the evidence for a decline is much stronger. It’s too soon to be sure – and a more detailed analysis will be conducted when we’ve finished data collection – but this clearly looks like a species we should be concerned about (as also indicated by USGS Breeding Bird Survey data from Connecticut and from eastern North America in general):

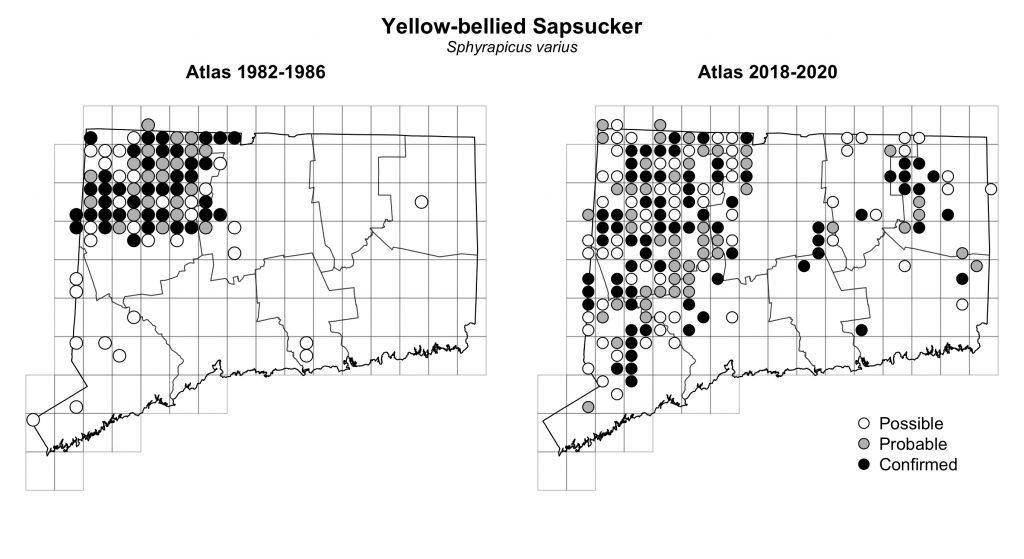

In contrast, as we’ve mentioned before, yellow-bellied sapsuckers are clearly spreading, both southward and eastward (I even have one drumming daily in my yard in Storrs):

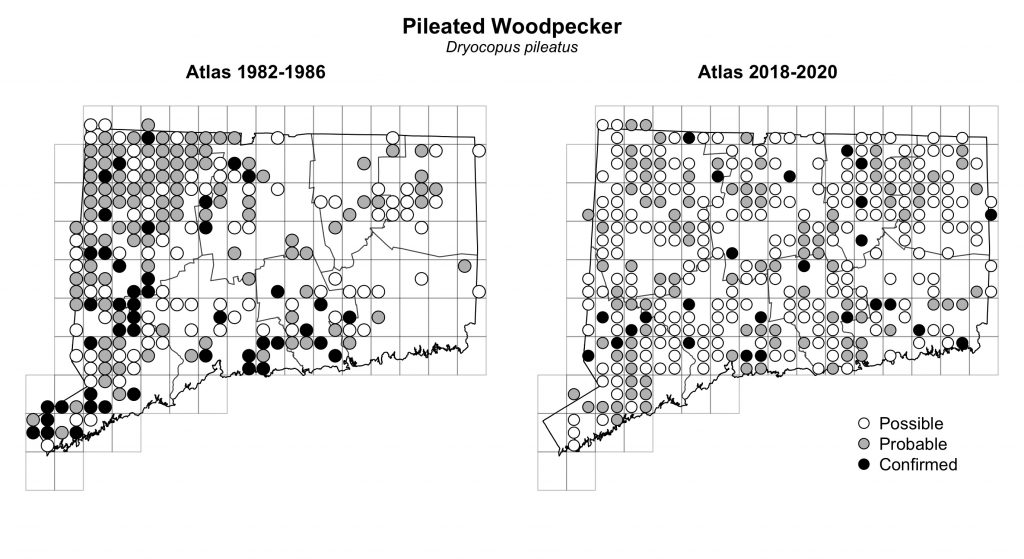

This sapsucker result is perhaps surprising as we expect species to be moving north not south due to climate change, and we often think of sapsuckers as being associated with more northern forests. A similar spread – especially the eastern expansion – is, however, also seen in pileated woodpeckers:

Taken together, the data for sapsuckers and pileated woodpeckers may indicate that forests are maturing and that there are simply more nesting options – bigger dead trees – for species that use well-forested landscapes, than was true in the 1980s. A similar argument could explain the eastward spread of hooded mergansers, which also nest in cavities in bigger trees.

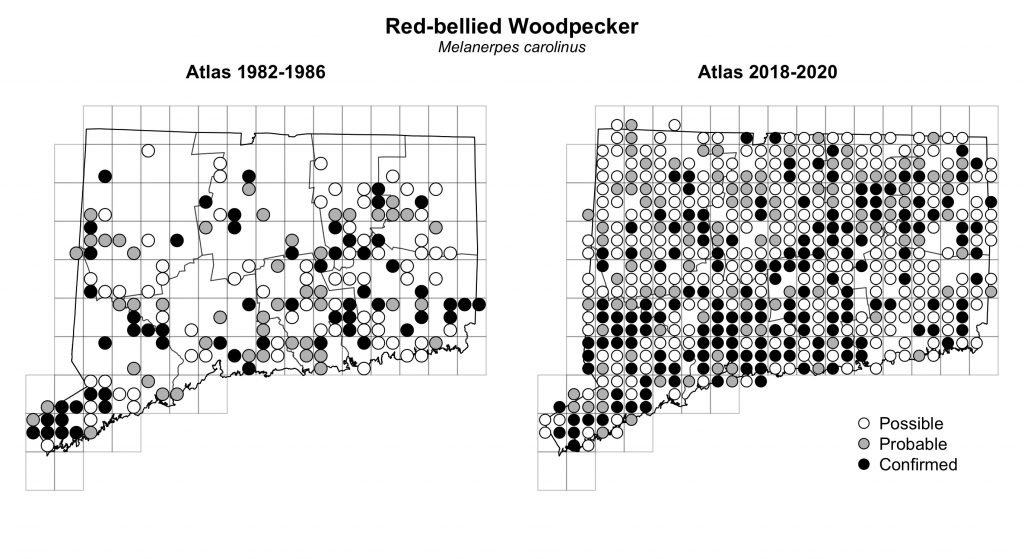

The last of the common woodpeckers, red-bellied, also shows a considerable expansion in range. In this case, the change is exactly what we would predict given climate change – a more southerly species moving north, and now found across the entire state.

As adults are feeding noisy nestlings, and young woodpeckers start to emerge from their nests, now is the ideal time to confirm breeding for woodpeckers. The next couple of weeks, then, provide a good opportunity to get out and look for these species if you haven’t yet recorded them in your area.