Yesterday, I posted on the need for more European starling breeding records. Today, it is the turn of house sparrows – perhaps the only Connecticut bird species disliked more (though there is another contender, which I’ll get to soon enough!).

Although house sparrows and starlings are introduced in North America and known to displace native species, understanding their population changes is important to our understanding of Connecticut’s ornithology. Both species are also undergoing dramatic population declines both here and elsewhere in the world. For example, most birders will have read the news reports a few months ago about the loss of 3 billion birds from North America over the past half century (original peer-reviewed article is here, unfortunately behind a paywall). It turns out that 330 million of those birds were house sparrows and another 80 million were starlings.

“So what?” you may ask, “they’re not supposed to be here anyway”. The problem is that something caused those declines, and even if the outcome is not a huge concern, the cause might be. For the number of house sparrows to decline by almost 80%, and starlings by almost half, something pretty serious is probably going on – and it is probably to our benefit to know what that is.

Little research has been done on the causes for the decline in North America, but the parallel declines in Europe have led to major research projects by organizations like the British Trust for Ornithology and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. These studies, and others, suggest that systemic changes in farmland and cities play key roles – and these changes likely have repercussions that go far beyond these two species. (This article provides a nice summary of the topic from a North American perspective.)

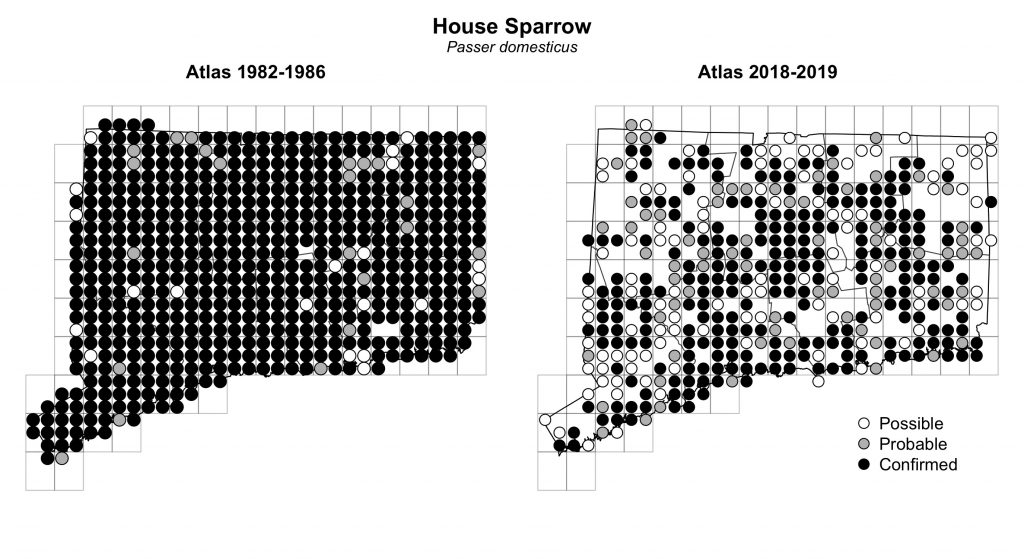

The Connecticut Bird Atlas is not going to answer fundamental questions about why these species are declining. But, by providing finer resolution on where birds have disappeared, and where they have not, it might give us clues as to what some of the issues are in southern New England. As is true for starlings, preliminary data show a surprisingly large number of blocks with no house sparrow records, and even more with no confirmed breeding:

Determining whether the gaps on the recent map are true absences requires only that we all make a concerted effort to check built-up areas and farms across the state. Finding house sparrow nests is not hard, as the adults are often obvious as they come and go, and their nests often protrude out of the cavities in which they are built (see photo above). Like starlings, house sparrows also begin nesting early in the year, and many already have young, such as this individual, which has the fleshy pale yellow gape and the raggedy, loose-feathered appearance that are typical of many recently fledged birds:

So, this is another species that can be easy to confirm as a breeder if they nest in your neighbourhood or in places you regularly frequent, such as your local grocery store or mall. And whatever you think of house sparrows, getting those confirmations will help us get the most of the atlas project.