The recent discovery of nesting sedge wrens at the Connecticut Audubon Society’s center in Pomfret, is perhaps the most exciting find of the atlas so far. But, although we hope to gain a better understanding of where rare species occur in the state, we also want to use the project to better understand the status of common species. With this in mind, here are a dozen species that it should be possible to confirm in nearly every block.

1. Song sparrow

2. American robin

3. Gray catbird

4. Black-capped chickadee

5. Mourning dove

6. Northern cardinal

8. House finch

9. Common yellowthroat

10. House sparrow

11. Chipping sparrow

12. Tufted titmouse

And with first broods starting to emerge from nests and second, or maybe even third, broods underway, the full range of breeding codes should be on display. For example, I see young robins, chipping sparrows, and catbirds nearly every time I go out atlasing, but I’ve also seen adults of all three species collecting nest material in the past week or so, suggesting that renesting is still underway. Other species, such as chickadees and titmice, have almost certainly stopped nesting, but can be seen in conspicuous family groups where the young birds can usually be picked out by their loose-feathered, fluffy-headed appearance or their rapid wing-fluttering behavior, designed to encourage their parents to feed them.

Eleven of these 12 species were among the 15 found in the greatest number of blocks during the first atlas, with all occurring in more than 98% of blocks. (The twelfth, tufted titmouse, was tied with chipping sparrow for the #15 position.)

Three of the remaining species – American crow, common grackle and European starling – should also be easy to confirm in most blocks, but I left them off the list, because we are no longer within their safe dates (or will be within a few days). The difficulty with these species is that, by this time of the year, they are starting to move around a lot and are not necessarily in the places where they bred. Fledglings are particularly troublesome because, although they indicate successful breeding, that success might have happened far from where the fledglings are seen – possibly in another block entirely. Confirming these species is still possible this summer, but it would require finding an active nest, or seeing very young fledglings that are clearly right out of the nest and still dependent on their parents.

The final species from the first atlas’s top 15 was a complete shock to me – northern flicker. Although flickers are not rare, I would never have guessed that they were found in 99% of blocks in the 1980s. But, this is a species that has undergone widespread population declines throughout much of its range. It will be interesting to see just how many atlas blocks flickers are found in during the current study.

Meanwhile, if you’ve not yet confirmed the 12 species on the list above, then take a little time this weekend to see if you can do so.

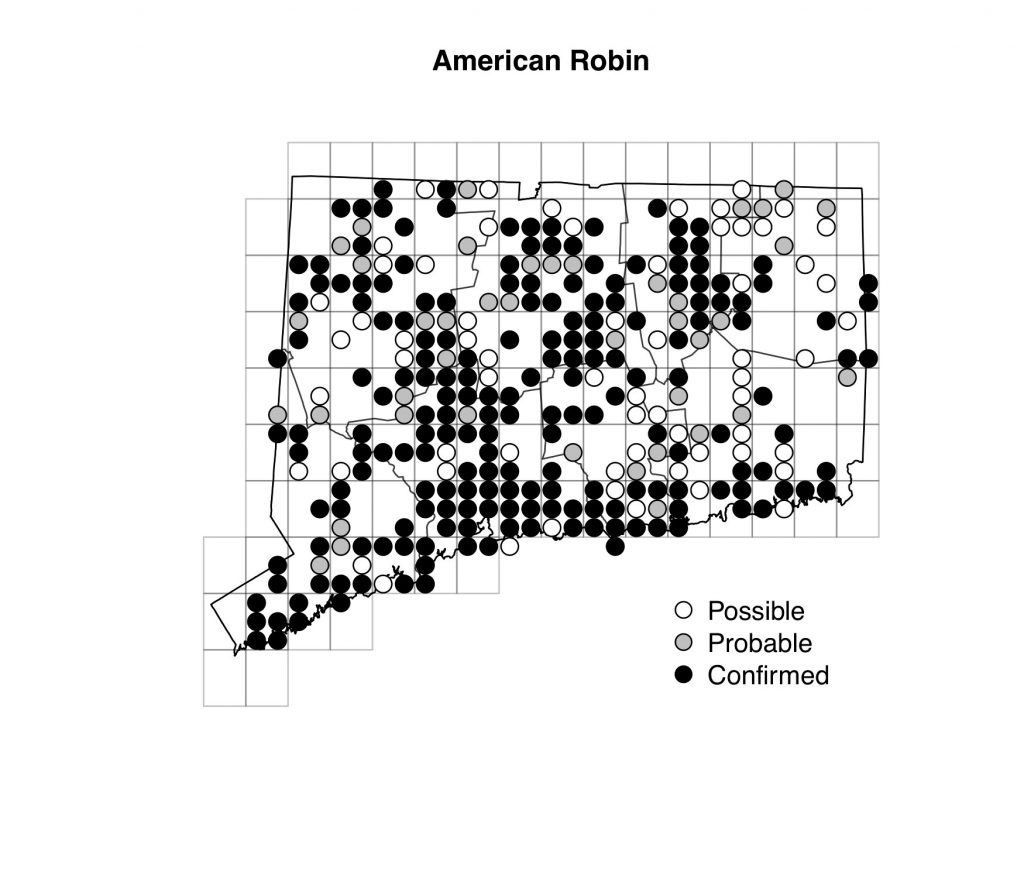

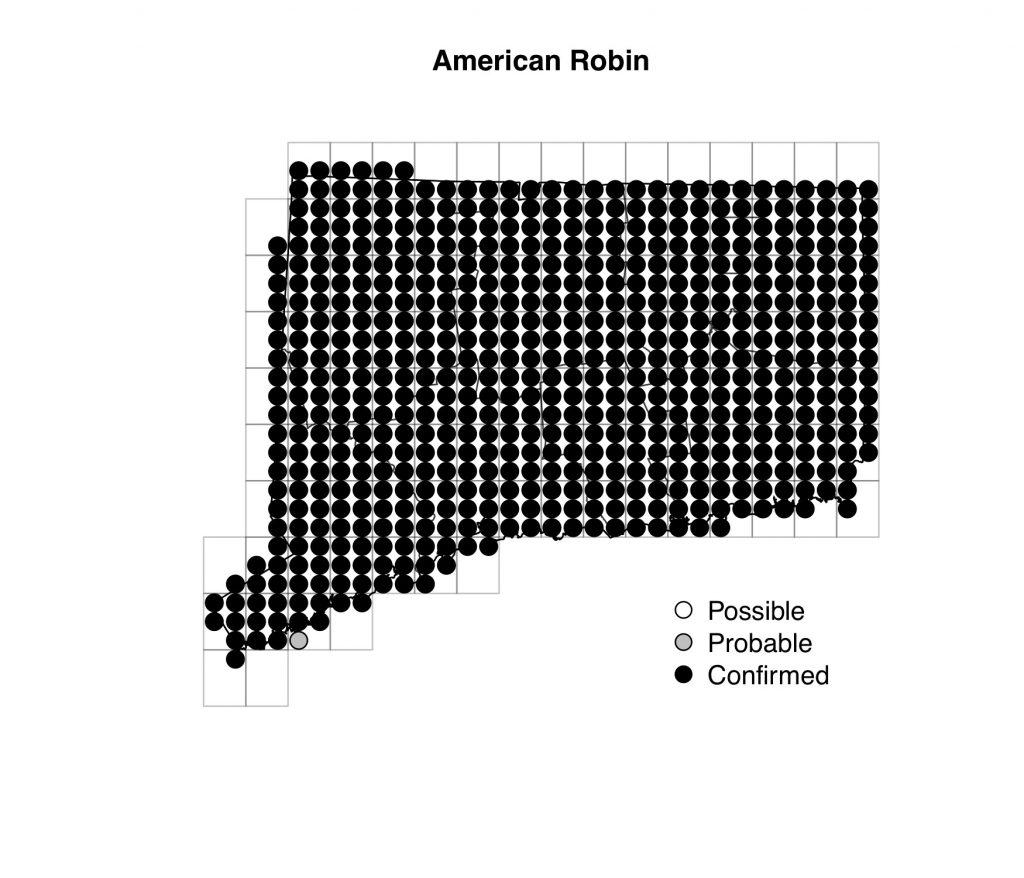

Preliminary breeding distribution data for American robin, showing records reported via eBird between the start of the 2018 breeding survey and early July 2018. Comparing this map to the one below, suggests that there are many more blocks in which it should be possible to confirm breeding for this species.

Breeding distribution data for American robin during the 1980s, from the first Connecticut Breeding Bird Atlas.